The response of many governments to the COVID-19 pandemic is transforming a public health emergency into a human rights crisis with serious social and economic implications (UN, 2020). International human rights law establishes that in the event of public emergencies threatening national security, restrictions on certain human rights can be justified, based on scientific evidence and, along non-discriminatory applications (UN, 1984). On the one hand, limitations to freedom of movement, including self-isolation and quarantine, are motivated by the widespread knowledge of the virus transmission via contact with droplets generated by infected people (WHO, 2020). On the other hand, several NGOs have pointed out to governments’ measures that, with the excuse of attending the crisis, do not meet international human rights laws, whilst further restricting the right to human dignity of marginalised groups.

The intellectual exercise of gendering the COVID-19 means addressing the construction of masculinities and femininities during the pandemic, drawing on a non-essentialist notion of gender as merely concerning women’s sex. For this purpose, feminist IR scholarship is particularly relevant for highlighting the gendered features of key concepts that are currently at the centre of the debate. First, it points out to the idea of the sovereign state as conceived along the idea of modern man who is rational and autonomous; second, it offers a definition of security which includes structural violence and environmental threats (Prugl and Tickner, 2018); third, it calls attention to the intersectionality of gender with other categories, including class, race, and geographical location (Crenshaw,1989).

State politics as toxic forms of masculinity

The effects of the global pandemic that we are currently witnessing well-reflect the contribution of feminist approaches to our understanding of COVID-19. A gender analysis demonstrates how the most powerful sovereign states are failing in handling this pandemic. For instances, by using the health crisis as a pretext to lurk into authoritarian governments (Cambodia, Israel, Bolivia, Hungary). An example is the bill sent by the Hungarian government to Parliament giving dictatorial powers to the prime minister, Viktor Orbán. This arrangement has caused many educated people, including doctors, to leave the country, thus further weakening an effective response to fight the pandemic (Applebaum, 2020). Such a political move finds itself within the realm of traditionally considered hypermasculine traits of self-interest and rational behaviours that still dominate global politics.

More importantly, it does not qualitatively differ, from the rhetoric employed by other world leaders, such as the US president Donald Trump and the Brazil president Jair Bolsonaro. Regarding the former, this has occurred by calling himself a ‘wartime president’ defending the country from an ‘invisible enemy’, whilst dismissing the seriousness of COVID-19 as an illness that could be simply cured by ingesting disinfectant (Osnos, 2020). Similarly, Bolsonaro pointed out to his manly history “as an athlete” as a protection from the virus (Dembroff, 2020). But where do patriotism, years of military spending vis-à-vis healthcare, and international isolationism can lead us during a global pandemic?

COVID-19 as a human right crisis

Perhaps, it is now becoming clear that the concept of national security as solely concerning the sovereign state is irrelevant in the context of a virus that continues infecting people regardless of their geographical location, class, sex and gender. Accordingly, the current global emergency represents the perfect example of how critical theory, including postcolonialism and postmodern feminism, offer a better explanation to world politics than more traditional IR theories relying on state centrism and the system. In particular, it seems pointless, at the moment, to rely on the understanding that the realist logic of absolute vis-à-vis relative gains may solve the global crisis. Reinforcing the discourse that COVID-19 is the ‘Chinese virus’, implying some sort of conspiracy against the US, may favour Trump’s government re-election. It is unlikely, however, that it will represent an effective solution to a structural threat, such as a pandemic.

Nevertheless, the persistence of great power politics at the international and domestic level still dominates. A consequence of this is that humans are dismissed as important actors in the global arena. At the same time, such a discourse has also favoured the idea that the COVID-19 emergency is a war, and as such should be countered. An enemy had to be identified and exclusionary narratives have been adopted by several countries- from India against the Muslims and the US against China. In a context of war, the reproduction of gender relations is still strongly linked to the traditional logic of ‘masculinist protection’ vis-à-vis ‘feminine denigration’ (Prugl and Tickner, 2018). Similarly, several sovereign states- which are the embodiment of rationality and self-defence (traditional masculine traits)- have relied on gender-based discrimination and other forms of human rights violations as a tactic to “encourage male fighting” (Ibid, 2018:78), thus ‘fight the virus’.

The narrative of war: insights for further analysis

The argument here is that attaching a traditional ‘war narrative’ to a global health crisis has implications for strategies that states will adopt to fight the virus. Even though it remains complex to draw generalisations on governments’ strategies against COVID-19 and compliance with human rights obligations, it is still plausible to say that the logic of war described in the above paragraphs is identifiable in the actions of, at least, some states’ leaders. It follows that a more attentive comparative analysis should take more variables into account, including the particular context, the manner of implementation, multiplicity of responses and norm inflation, and political and judicial review (Acosta et al., 2020).

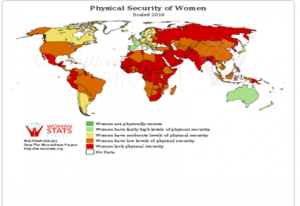

As much of feminist literature argues, patriarchal gender relations predispose states- more than the presence of a democratic rule- to war (Cockburn, 2009; Caprioli, 2003). Therefore, it is the significance attached to masculinities- exacerbated during militarisation- that allows for the reproduction of patriarchy (Cockburn, 2014). In this sense, we could assume that countries with higher levels of patriarchal norms are more likely to engage with the discourse of the COVID-19 pandemic as a war, thus be less likely to comply with international laws and commit and/or allow human rights violations. We can consider as indicator to variation of patriarchy across countries, Mary Caprioli’s scale of physical security of women (Fig.1).

Human rights discriminations during a global pandemic

By looking at the map, we can start to offer some examples of states engaging with the narrative of war whilst discriminating marginalised groups. In several US states, lawmakers have declared abortion as “nonessential”. The global crisis was also the opportunity for President Trump to reverse Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act passed during the Obama administration, imposing doctors, hospitals, and other health care workers to give care to anyone regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity (Burns, 2020). In many have pointed out to the immorality of realising such a rule in the middle of a pandemic. It brings the danger of further threatening the well-being of trans people by putting them at the whim of doctors’ personal beliefs (Ibid, 2020).

In addition to these two examples, India represent another case where right-wing Hindu politicians have, in more instances, referred to coronavirus as a Muslim disease with television channels declaring war on a “corona jihad” (Findlay and Singh, 2020). Since the Modi administration took office, anti-Muslim remarks have been characterising speeches and interviews. The citizenship law amendments passed in December 2019, in particular, was already described as a discriminatory measure against Muslims and a violation of international human rights laws by the Human Rights Watch (2020). With the COVID-19 outbreak, this propaganda has resulted in an increase of incidents of violence against the Muslim minority, arbitrary arrests, and limits of access to legal assistance (HRW, 2020).

Controlling the pandemic: machismo in global politics

International human rights organisations need to be particularly attentive to the case-by-case monitoring of human rights. An important difficulty lies in guaranteeing that the judicial review extends to all the measures taken by individual governments, also those introduced after declaring the state of emergency (Acosta, 2020 et. al). At the same time, it is also necessary to develop effective strategies for controlling the pandemic.

As a threat to international security, a global pandemic highlights the importance of human security approaches. The latter envisage security as strongly linked to the human experience of a certain catastrophe as opposed to the dominant narratives on state politics. In accordance to this view, feminist theory recognizes the variation of masculine identities across different world leaders (Cockburn, 2010; Hearn, 2012). In other terms, decision and policies enacted by states are to be understood as a result of the construction of gender identities. Even though this article does not contain a comparative analysis for the effects of masculine identities on the rise of human rights violations and gender-based discriminations, it does offer insights for further research. This may take into account the proposed assumptions. In particular, the idea that states engaging with the narrative of COVID-19 as war may be less likely to comply with international laws on human rights.

It is now common belief among many that a global crisis requires a global action. Accordingly, this requires states’ leaders to rely on collective strategies which are based on the traditionally feminine traits of solidarity, empathy, and listening. To date, many world leaders have decided to prioritise their own political interests. As the examples of China, Hungary, and the US have shown, these are informed by their respective hypermasculine identities. Yet, such political initiatives turn out to be incompatible with effective strategies for controlling COVID-19.

Coronavirus and women

After nearly two months of lockdown, Italy entered the so-called ‘phase 2’ on May 4thwith about 2.7 million Italians returning to work. Yet, among these, the 72% is constituted by men despite the fact that in Italy women have more professional qualifications, and more than half of all Italians getting a degree are women (59%) (The Local, 2018). Furthermore, several studies have also pointed out to a sharp decrease in women’s productivity- in terms of solo-authored submissions of academic articles (Flaherty, 2020). On the other hand, the co-editor of Comparative Political Studies saw, in April, an increase of the 25% in journal submission. The latter being entirely driven by men.

A first analysis of these data may lead us into thinking that the lockdown required women to embody their traditionally gender roles as caregivers. This does not necessarily mean that at home men do not help at all, but that, on average, women take on more service work and are less protective of their actual work time (Flaherty, 2020). It is also plausible to assume that there was not a sharp shift in this sense. Therefore, in pre-lockdown times caregiver positions within the household were already held by women, such as babysitters or housekeepers. The Coronavirus outbreak has simply exacerbated pre-existing inequities at the domestic and employment levels. In a context like Italy, these are also the consequence of gender unequal family, child care, and labour policies.

Silvia Romano

This article concludes by considering the return of the Italian aid worker Silvia Romano- held hostage in Somalia for 18 months by an al-Qaeda linked terrorist group. Her stepping off the plane in Rome, wearing a hijab has been even described as Jew returning home from a concentration camp dressed as a Nazi (Il Messaggero, 2020). Romano’s conversion to Islam is still a source of controversy in Italy, with many political figures and journalists using hate speech against her and reinforcing the discourse that that her conversion to Islam makes of her a ‘neo-terrorist’. The violence inherent in these accusations- that do not consider her personal and traumatic experience- are to be criticized from all points of view. Not only do they confuse the difference between Islam and terrorism, but they also neglect the body of the experience.

Once again, a woman has become object of discrimination for a personal choice over her body and spirituality. Claims that the Italian government paid a ransom of millions of euro for Romano’s release have further exacerbated the anger of many Italians who are suffering the economic consequences of a national lockdown. Would such an extended use of gender-based violence been used also in ‘normal times’? By looking at the parallel cases, one could argue that also in the absence of a global pandemic Silvia Romano would have received harsh criticism.

It should be everyone’s responsibility to recognise that the verbal attacks against Silvia Romano represent a gender-based discrimination. It was not socially acceptable for a woman that was kidnapped in Somalia to return home with a smile on her face and wearing a hijab. These characteristics make of her a marginalised individual within society: she is a woman, she refuses the role of the victim, and she has chosen to be Muslim.

Conclusion

To date, it seems that the COVID-19 pandemic is leading even more to discriminations against women and other marginalised groups. The realisation that a collective action, based on empathy and solidarity, is the only effective response to control the pandemic, however, brings the potential of a change at the systemic level. More decision-making positions should be held by women who play an essential role in the establishment of more equal and representative societies. Yet, this remains a long and difficult process that require a collective acknowledgment. Only opening the discussion, among our peers, in our everyday, can highlight the systemic reproduction of gender stereotypes and, represent a first step towards more positive gender paradigms.

Bibliography (A-G)

Acosta, A. et al. (2020). Controlling the Pandemic, guaranteeing rights. LSE Blog, April 27. Available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/wps/2020/04/27/controlling-the-pandemic-guaranteeing-rights/

Applebaum, A. (2020). The People in Charge See and Opportunity, The Atlantic, March 23. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/when-disease-comes-leaders-grab-more-power/608560/

Burns, J. (2020). States that Use COVID-19 to Ban Abortion Increase Our Risks, Hardships and Fear Nationwide. Forbes, April 12. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/janetwburns/2020/04/11/states-using-covid-19-to-ban-abortion-increase-everyones-risks-and-hardships-in-a-crisis/#717aaf60aa8c

Burns, K. (2020). The Trump administration could soon allow doctors to discriminate against LGBTQ people. Vox, April 24. Available at: https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/4/24/21234532/trump-administration-health-care-discriminate-lgbtq

Caprioli, M. (2003) ‘Gender Equality and State Aggression: The Impact of Domestic Gender Equality on State First Use of Force’, International Interactions. Routledge, 29(3), pp. 195–214. doi: 10.1080/03050620304595.

Cockburn, C. (2010) ‘‘Militarism and War.’’ In Gender Matters in Global Politics. A Feminist Introduction to International Relations, edited by Laura Shepherd, 105–15. London, UK: Routledge.

Cockburn, C. (2014). Feminist Antimilitarims. In Geuskens, I. eds Women Peacekmakers Program, pp. 33-35. Available at: http://www2.kobe-u.ac.jp/~alexroni/IPD%202015%20readings/IPD%202015_9/Gender%20and%20Militarism%20May-Pack-2014-web.pdf

Crenshaw, K (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989 (1), pp. 139–67. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf

Dembroff, R. (2020). In this moment of crisis, macho leaders are a weakness, not a strenght,The Guardian, 13 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/13/leaders-trump-bolsonaro-coroanvirus-toxic-masculinity

Fareedi, G. (2020). Opinion- Challenges to the Realist Persepctive During the Coronavirus Pandemic, E-International Relations, May 6. Available at: https://www.e-ir.info/2020/05/06/opinion-challenges-to-the-realist-perspective-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

Flaherty, C. (2020). No Room of One’s Own. Inside Higher Ed, April 21. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/04/21/early-journal-submission-data-suggest-covid-19-tanking-womens-research-productivity#.XqBQyGoiyNI.twitter

Findlay, S. and Singh, J. (2020). India cracks down on Muslims under cover of coronavirus, Financial Times, May 4. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/34ad9282-74d7-4a85-a629-a9655339c366

Bibliography (H-Z)

Hearn, Jeff (2012) ‘‘Men/Masculinities: War/Militarism—Searching (for) the Obvious Connections?’’ In Making Gender, Making War: Violence, Military and Peacekeeping Practices, edited by Annica Kronsell and Erika Svedberg, 35–51. New York: Routledge.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2020). Human Rights Dimension of COVID-19 Response. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/19/human-rights-dimensions-covid-19-response

HRW (2020). “Shoot the Traitors”. Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy, April 9. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/04/09/shoot-traitors/discrimination-against-muslims-under-indias-new-citizenship-policy

Il Messaggero (2020). Silvia Romano, post choc del consigliere leghista Angelosante: “Mai sentito di ebrei liberati convertiti al nazismo in abiti SS?” Available at: https://www.ilmessaggero.it/abruzzo/silvia_romano_consigliere_leghista_nazismo_simone_angelosante_ultime_notizie_11_maggio_2020-5221039.html

Osnos, E. (2020). The folly of Trump’s blame-Beijing Coronavirus strategy. The New Yorker, May 18. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/05/18/the-folly-of-trumps-blame-beijing-coronavirus-strategy

Phelan, J. (2018). 12 statistics that show the state of gender equality in Italy. The Local, March 8. Available at: https://www.thelocal.it/20180308/statistics-women-in-italy-womens-rights-gender-gap-equality

Prugl, E. and Tickner, J. A. (2018). Feminist international relations: some research agendas for a world in transtion. European Journal of Politics and Gender, 1(1), pp. 75-91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1332/251510818X15272520831193

Stachowitsch, S. (2015) ‘The Reconstruction of Masculinities in Global Politics: Gendering Strategies in the Field of Private Security’,Men and Masculinities, 18(3), pp. 363–386. doi: 10.1177/1097184X14551205.

The WomanStats Project (2019). Viewed 12 May 2020, < http://www.womanstats.org/index.htm>

Kingsely, M. (2020). Lockdown is threatening hard-won gains for women, Brisbane Times, April 27. Available at: https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/lifestyle/gender/lockdown-is-threatening-hard-won-gains-for-women-20200424-p54n32.html

Kretchmer, H. (2020). 6 ways to protect human rigths during lockdown- according to the UN. World Economic Forum, 1 May. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/un-human-rights-coronavirus-lockdown?fbclid=IwAR1el3w0AUEhBg6ho3IigrSbwolXKu1BPvZQyJMzJJ3NK5J0WWCr2Oct_JA

World Health Organisation (2020). https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

United Nations (2020). Covid-19 and Human Rigths. We are all in this together, April. Available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_policy_brief_on_human_rights_and_covid_23_april_2020.pdf

UN Commission on Human Rights, The Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 28 September 1984, E/CN.4/1985/4, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4672bc122.html [accessed 9 May 2020]

***

Autore dell’articolo*: Ginevra Canessa, studentessa in Politics and International Relations, BA (Hons), University of Kent (Regno Unito). Addetta alle questioni di Global Gender Justice della Think Tank.

***

Nota della redazione del Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

Come sempre pubblichiamo i nostri lavori per stimolare altre riflessioni, che possano portare ad integrazioni e approfondimenti.

* I contenuti e le valutazioni dell’intervento sono di esclusiva responsabilità dell’autore.

Editor’s Note – Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

As always, we publish our articles to encourage debates, and to spread knowledge and original and alternative points of view.

* The contents and the opinions of this article belong to the author(s) of this article only.