The rising role of climate change in peacebuilding activities

In the last years, analysts have stressed how peacebuilding activities are becoming more challenging in those areas strongly affected by climate change effects (Crawford et al, 2015). Those may increase the economic, social and political instabilities in post-conflict countries jeopardizing the international efforts to maintain peace (Krampe, 2019). As the UN former Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon noted, climate variation could be a threat multiplier, influencing different conflict drivers such as: historical grievances, wealth disparities, economic instabilities or weak governance (Sheffran et al, 2009). Although climate change is not the only cause of conflict, it is a relevant catalyst for tensions especially in fragile countries (Brown & Crawford, 2009).

Highlighting how 80% of countries hosting the highest amount of multilateral peace operations personnel in 2018 are placed in regions exposed to climate change, SIPRI data confirms the importance of climate change adaptations for peacebuilders (SIPRI, 2019), especially considering the presence of fragile institutions in those states. Despite being the least responsible of climate variation, these countries are considered where climate-related conflicts are most likely to emerge and where multilateral intervention could face more challenges (Brown & Crawford, 2009).

As matter of fact, the economic reliance on climate-dependent sectors (particularly rain-fed agriculture) and the previous social and economic grievance increase the fragile state vulnerability to climate change (Crawford et al, 2015). Beyond highlighting the link between climate change and conflicts in fragile states, this paper focuses on the importance of climate-resilient peacebuilding intervention taking in consideration climate change as short and long term conflict driver.

The links between climate change and conflicts

Despite the high number of contributes explaining links between conflict and climate change, there are still some difficulties to fully understand the complex relations among the mentioned factors (Smith & Vivekananda, 2007; Tänzler, Maas & Carius, 2010;). In general, researchers commonly agree that climate change may be an element (more or less significant taking in consideration the background) for potential social, political and economic disputes (Matthew & Hammill, 2012; Barnett & Adger, 2007). In particular, climate change, as “threat multiplier”, could accelerate: the increment of people displaced, the stress on local and national institutions and the competition for natural resources.

About the first threat, climate variations such as rising sea level or declining rainfall in arid locations could generate a significant movement of people within and between countries, creating potential conflicts between host and migrant populations (Brzoska & Fröhlich, 2016). The Somali case in 2018 is a clear example of that, when flash floods affected more than 695 000 people, displacing nearly 215 000 (Middleton et al, 2018).

Moreover, climate change stresses some important economic sectors such as health, water, food and energy systems, jeopardizing the work and legitimacy of weak institutions. An example of that is the conflict in northeastern Nigeria in the Lake Chad area (Okpara et al, 2019). Years of drought and food insecurity increased the people’s lack of confidence in national and local authorities unable to invest in the area. This background favorited the presence of Boko Haram group which has been able to recruit young men with few livelihood options.

In the end, climate change could be a source of conflict within and between states, considering how climate instability intensifies the scarcity of the most important resources for local people. Following some studies, the increment of local conflicts in the Lake Victoria Basin can be linked to water scarcity due to climate change (Mwiturubani, 2010).

The climate change negative effects on fragile states

Even though there is no agreed definition of what constitutes a fragile state, this could be defined as a country where governments are not capable of assuring basic security to their citizens, cannot maintain the rule of law and justice and are not able to provide basic services and economic opportunities for the population (Mcloughlin, 2012).

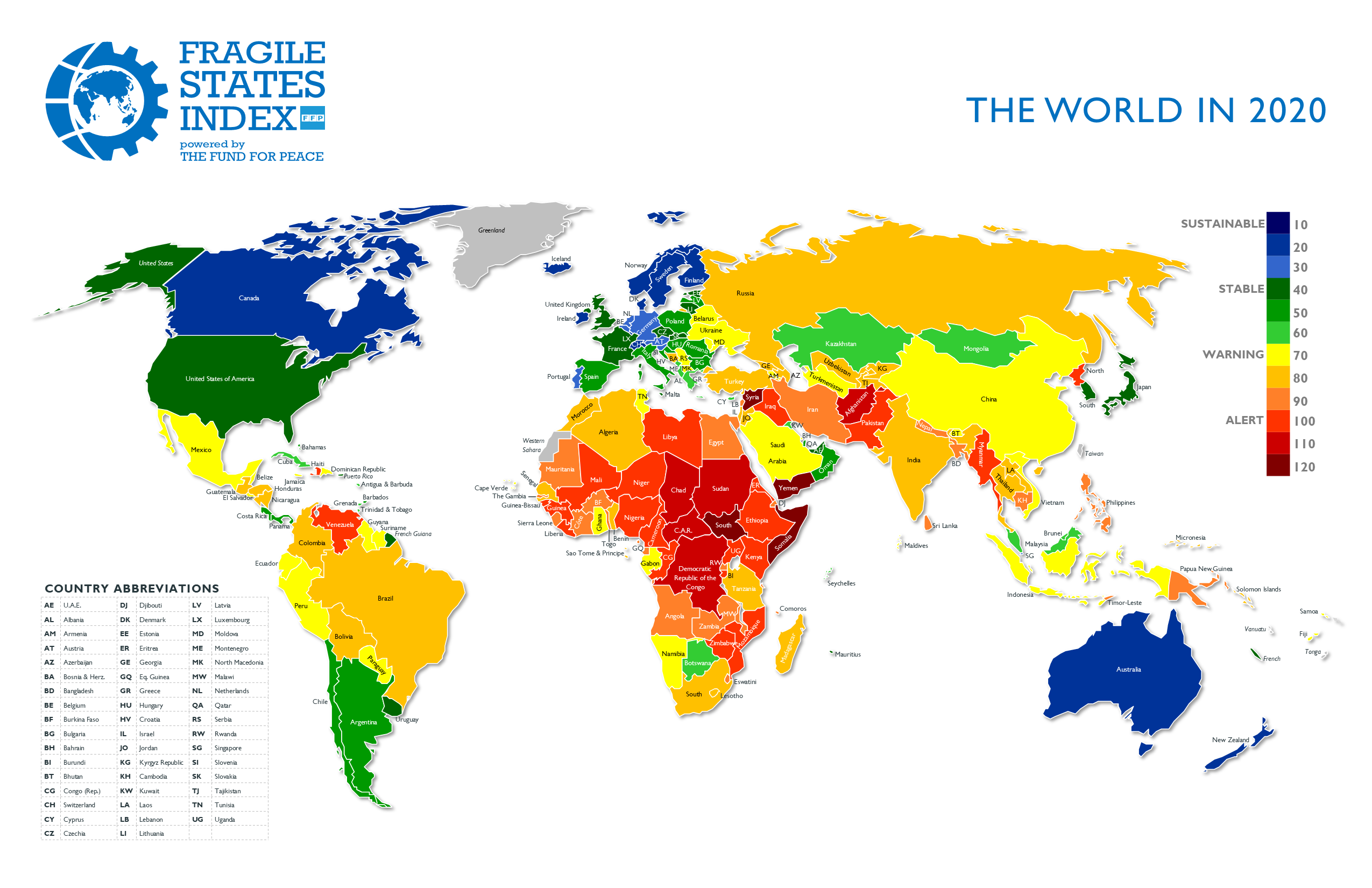

The causes of fragility are various and often context specific. A good approach to recognize the source of state fragility is the Fragile State Index launched by the Fund for Peace (the Fund for Peace 2020). This annual classification uses the following 12 indicators which can be also considered the causes of fragility: demographic pressures, the presence of refugees and internally displaced persons, group grievances, human flight and brain drain, uneven economic development, poverty and economic decline, state legitimacy, the provision of public services, the respect of human rights and rule of law, the security apparatus, the presence of factionalized elites, and the intervention of external actors.

Taking in consideration Political, Social and Economic indicators, the Fund for Peace shows the risk and vulnerability in 178 countries

Considering the mentioned indicators and causes, the fragile state context proves to be complex with different variables. In this background, there is a great potential for climate change to cause further instability (USAID, 2009). Limited capacity of governments, the reliance on climate- sensitive sectors and geographic location (such as the the Horn of Africa, the Sahel, south Asia and the Middle East) transform fragile states into really exposed scenarios to the climate change effects. As matter of fact, climate variation may stress the capacity of households, communities and governments to cooperate responding to the challenges presented in these backgrounds (Barnett & Adger, 2007).

Moreover, the risk of vicious cycles between conflicts and climate change impacts seems higher in fragile states where existing conflicts restrict the capacity of communities or institution to effectively respond to climate change escalating climate variation impacts (Crawford et al, 2015).

Peacebuilding activities in fragile states, issues and difficulties

Taking into account the previous factors, international organizations are aware of how costly and complex it is to work in fragile states or post conflict areas (DFID, 2009). Rapid changes in operating contexts, weakened governance frameworks, damaged or destroyed infrastructures, lack of info and difficulties to find local partners are only some of the multiple challenges faced by multilateral operations (Crawford et al, 2015). In these backgrounds, climate variation is able to negatively influence the peacebuilding targets, such as those ones related to peace and security safeguard, governance strengthening and social and economic development.

One of the most evident cases is Somalia, where the peacebuilding process has faced relevant issues in the mentioned sectors, also caused by climate change. In relation to peace and security, the 2018 flash floods in Somalia affected more than 695 000 people, displacing nearly 215 000 (Krampe, 2019). Many IDPs (internal displaced people) moved to the biggest urban centers to live in camps which became recruitment ground for Somalia’s dominant insurgent group, Al-Shabaab (Middleton et al. 2018). This created several troubles to the efforts of the United Nations and African Union to mitigate Al-Shabaab activity in the area (United Nations Security Council Resolution 2461, 27 Mar. 2019.).

As well, the IDPs flows in the city of Baidona in south-western Somalia jeopardized the institutional legitimacy, undermining the the efforts of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) to find an agreement with local groups. In the end, following some local and international data (Federal Government of Somalia et al, 2018) the 2016, 2017 and 2018 droughts could seriously affect the economic long term development.

The peacebuilding approach, six principles for the future

As the Somali case shown, the modern bottom-up approach to peacebuilding could be more sensitive to the context changes generated by climate change. In general, multilateral peacebuilding efforts do not seem prepared to handle the fact that climate change is affecting the key sectors and elements of their activities and mandates. Considering this peacebuilding interventions should be more climate-sensitive to be better prepared in the new challenges raised by climate change. In this background, a relevant work has been developed by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Gathering data and experiences from practitioners, this institute draw six useful principles which could improve the peacebuilding action for a sustaining peace.

Following the IISD data (Crawford et al, 2015), in order to achieve an integration for climate resilient peacebuilding, the international efforts should cover these points: a) Use integrated context analysis as the foundation for planning; b) Balance immediate and long-term priorities; c) Address climate-natural resource-conflict linkages; d) Facilitate coordination across disciplines, sectors and levels; e) Adopt a forward-looking approach to planning; f) Aim for resilience as an overarching objective. Only considering all these points, an international peacebuilding operation can operate in fragile states mitigating the climate change negative effects.

Implementing the principles, which policies to adopt for a sustaining peace

In order to implement the mentioned principles, three aspects are particularly relevant. Considering how climate change has a multifaceted impact, it is fundamental to improve the coordination among all peacebuilding actors, exchanging their experience and knowledge. The methodological and regular collection of common experiences and best practices among entities could favourite joint and most efficient responses.

Secondly, taking into account the importance of climate change as a threat multiplier in fragile states, peacebuilders should know how climate – related issues can influence contexts where they are working. This essential part of the background assessment should investigate the climate adaptation project risks to the prospects for peace; the risks that come from climate insensitive peacebuilding and development interventions and the risks climate change generates for peacekeeping, peacebuilding and conflict prevention activities.

In the end, peacebuilders should identify multiple ways to create integrated strategies responding short-term emergencies and long-term development needs. Following this approach, projects for climate change adaptation are not only a way to mitigate the mentioned risks, but they are also opportunities to promote a sustaining peace (Krampe, 2016)

Conclusions

Although there is an increasing awareness that climate change, as “threat multiplier”, will amplify the problems of peacebuilding activities, especially in fragile states, international efforts to build peace still do not take into account climate variation effects. Those have a special impact in fragile states, which are particularly exposed to climate change due to their characteristics. In order to improve peacebuilding efficiency, mitigating the mentioned issues, international efforts should integrate their bottom-up approach, considering climate change as a fundamental key factor for the short and long term social, economic, political risks and development.

Bibliography A-L

Barnett, J., & Adger, W. N. (2007). Climate change, human security and violent conflict. Political geography, 26(6), 639-655.

Brown, O., & Crawford, A. (2009). Climate change and security in Africa. Climate change and security in Africa.

Brzoska, M., & Fröhlich, C. (2016). Climate change, migration and violent conflict: vulnerabilities, pathways and adaptation strategies. Migration and Development, 5(2), 190-210.

Crawford, A., Dazé, A., Hammill, A., Parry, J. E., & Zamudio, A. N. (2015). Promoting climate-resilient peacebuilding in fragile states. Geneva: International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

DFID. (2009). Political economy analysis how to note, a practice paper. London: Department for International Development. Retrieved from http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/events-documents/3797.pdf

Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), World Bank (WB), United Nations (UN) and European Union (EU), Somalia Drought Impact & Needs Assessment, vol. 1, Synthesis Report (FGS, WB, UN and EU, 2018).

Krampe, F. (2019). Climate change, peacebuilding and sustaining peace.

Krampe, F., ‘Water for peace? Post-conflict water resource management in Kosovo’,

Cooperation and Conflict, vol. 52, no. 2 (2016) pp. 147–65.

Bibliography M-Z

Matthew, R., & Hammill, A. (2012). Peacebuilding and adaptation to climate change. Assessing and restoring natural resources in post-conflict peacebuilding, 267-282.

Mcloughlin, C. (2012). Topic guide on fragile states. Birmingham, UK: Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, University of Birmingham.

Middleton, R. et al., Somalia: Climaterelated Security Risk Assessment (Expert Working Group on Climate-related Security Risks: Stockholm, 2018).

Mwiturubani, D. A., & Van Wyk, J. A. (2010). Climate change and natural resources conflicts in Africa. Institute for Security Studies Monographs, 2010(170), 261.

Okpara, Ut., Stringer, L.C. & Dougill, A.J. 2016. Lake drying and livelihood dynamics in Lake Chad: Unravelling the mechanisms, contexts and responses. Ambia 45: 781-795.

Scheffran, J., Brzoska, M., Brauch, H. G., Link, P. M., & Schilling, J. (Eds.). (2012). Climate change, human security and violent conflict: challenges for societal stability (Vol. 8). Springer Science & Business Media.

SIPRI Multilateral Peace Operations Database, 2019, available online at: www.sipri.org/databases/pko.

Smith, D., & Vivekananda, J. (2007). A climate of conflict: The links between climate change, peace and war. International Alert.

Tänzler, D., Maas, A., & Carius, A. (2010). Climate change adaptation and peace. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(5), 741-750.

The Fund for Peace (2020). Fragile state index. available online at https://fragilestatesindex.org/

***

Autore dell’articolo*: Mario Ghioldi, Dr. in International Studies and Diplomacy presso L’Università degli Studi di Siena; Master in Diritti Umani presso SIOI.

***

Nota della redazione del Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

Come sempre pubblichiamo i nostri lavori per stimolare altre riflessioni, che possano portare ad integrazioni e approfondimenti.

* I contenuti e le valutazioni dell’intervento sono di esclusiva responsabilità dell’autore.

Editor’s Note – Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

As always, we publish our articles to encourage debates, and to spread knowledge and original and alternative points of view.

* The contents and the opinions of this article belong to the author(s) of this article only.