![]() from Rome, Italy

from Rome, Italy

DOI : 10.48256/TDM2012_00147

Introduction

Social infrastructures are one of the pillars of society’s well being and security, since their function is to meet basic needs and support economic growth. Indeed, social infrastructures have been at the forefront of past months’ news, unfortunately not for praise, but because the recent COVID-19 pandemic shed light on their systematic and structural criticalities. Indeed, hospitals and healthcare facilities played a crucial role in the fight against the virus, while schools and education facilities were forced to close for months and, still today, they are trying to cope with new rules and necessities. Same is the situation of prisons that, during the outbreak, did not have suitable spaces to house inmates while respecting emergency measures.

It is clear that social infrastructures needed to be further developed, modernized, adapted to new technologies even before the COVID-19 pandemic spread; yet, today this need is even more amplified.

However, most Nation States do not possess public financial resources necessary to start such operations all by themselves; consequently, it is vital to look at alternatives and find different sources of capital than public finances. A possible option can be to look at private capital attraction.

This is why this article will focus on one specific opportunity, the one represented by the profitable financial synergy that can flourish between institutional investors and social infrastructures.

Indeed, between this class of investors and the proposed asset class, there can be a fruitful match, advantageous to exploit most of all today after COVID-19 pandemic, when infrastructures still need to be built and refurbished, but also rethought and technologically advanced.

EU social infrastructures and their investment funding gap

Infrastructures are “[…]the basic systems and services, such as transport and power supplies, that a country or organization uses in order to work effectively” (Cambridge Dictionary). In turn, infrastructures can be divided into two subsets: economic and social infrastructures. While the firsts are defined as “[…] internal facilities of a country that make business activity possible, such as communication, transportation, and distribution networks and others” (Business Dictionary), the latter are “[…] a subset of the infrastructure sector that can broadly be defined as long-term physical assets in the social sector that enable goods and services to be provided” (Fransen et al., 2018). Their main objective is to support life quality and wellbeing of citizens and communities in a nation. They comprise health and education, social housing, security and defense infrastructures, public buildings, culture and entertainment facilities and many others.

For a long time, social infrastructures in Europe have been financed only through public finances: indeed, the essential services that they provide may constitute civil rights and, therefore, they had to be provided for free. However, even before the economic and financial crisis, European countries, regions and municipalities were confronting a chronic lack of investments in social infrastructures. Indeed, net public investment in the Eurozone periphery decreased from 2% of GDP to a negative –0.6% (Fransen et al., 2018). This data means not only the absence of further public investments in the sector, but also that the public capital stock already existing was undergoing a shrinking process, ultimately adversely affecting countries’ competitiveness and future generation’s opportunities.

Finally, differences in EU Countries’ social infrastructure stocks, both in terms of volumes and quality of performances, contribute to increased inequalities and to trigger a process of economic divergence among European Member States.

Quantifying the gap

How large is this gap in Europe?

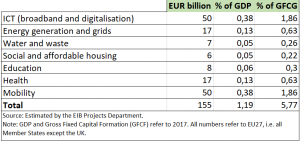

The first attempt to quantify this amount was undertook by the European Investment Bank (EIB) with a 2018 report, which estimated the 2017 infrastructure investment gap for the EU27 (i.e. all Member States except the UK) until 2030 at roughly €155bn. (which represents 1.2% of EU GDP). Data are reported on the table below; from there, it is possible to identify the gap related to the three main social sectors, namely health, education and social and affordable housing. These constitute up to €31bn (0.24% of GDP) and so, one fifth of the total annual gap.

2017 Annual infrastructure investment gaps for EU27

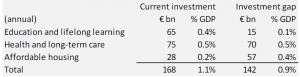

However, other studies report much more pessimistic findings: Fransen et al. (2018) estimated that the current annual European investment in social infrastructures accounts for approximately €170 billion (around 1.1% of GDP), needing a further minimum investment of €100-150 billion per year (0.7-1% of GDP) till 2030.

Current investment and investment gap in social infrastructure per year

Finally, SDA Bocconi (2018) identified an investment gap of €477bn in the healthcare sector, and a gap of €509bn in the education sector, over the next 20 years. This would correspond to a combined investment gap in the two sectors of about 0.3% of GDP.

Therefore, despite in the past they have been prevalently publicly financed, nowadays social infrastructures need an amount of investments that most Nation States cannot provide. Moreover, European Countries most in need to develop and refurbish their infrastructures, are also those that present higher public debts. The European Commission is helping States most affected by COVID-19 crisis with extraordinary economic and financial measures; however, a parallel opportunity may come from the attraction of private capitals, like those of institutional investors.

Who are institutional investors?

Institutional investors are defined as “[…] specialized financial institutions that mobilize and manage savings of individual investors and institutions and invest on financial markets, depending on their risk profile, aims and investment horizon, all with the aim to increase investment value” (Krišto and Stojanovic,2014).

Institutional Investors are a heterogenous group, composed of pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds (SWF), endowments, fund managers and wealth managers. Usually, they seek investment opportunities that entail long-term, stable returns, which are inflation-protected and which displays low volatility.

For a long time, their attention was directed mainly toward bonds and equities; however, in the last years, their quest for diversification brought their attention toward emerging markets and new asset classes, like infrastructures, real estate, private equity, cash and others.

Institutional investors have a considerable impact on financial markets, determining stock prices and profitability and being a considerable source of liquidity; also, their assets under control experienced a rushing increase during last years. Then, they influence even the real economy, since their investments represent sources of financing for growth and development of small and medium-sized enterprises, for overcoming some countries’ infrastructural gaps and, finally, for addressing the challenge of climate change, just to cite some examples.

Institutional investors increasing international role

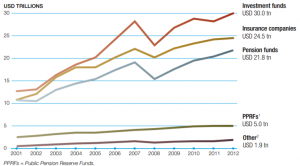

As of today, worldwide Institutional investors control assets over $130 trillion (Inderst, 2020). An OECD survey found that their Assets Under Management (AUM) is equal to or higher than the GDP of many OECD countries. In particular, pension funds in OECD countries passed from managing assets of about $15,4 trillion in 2008 to $21,8 trillion in 2012.

Total assets by type of institutional investor in the OECD, 2001-2012

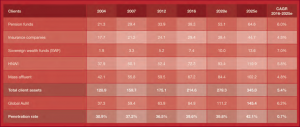

In addition, PWC estimated that AUM of all institutional investors in the world will hit $145 trillion before 2025.

Institutional Investors AUM Trend in USD trillion, 2004-2025

Hence, capital hold by institutional investors is already significant and it is forecasted to increase even more in the near future. If this capital would be employed in investments in the sector, social infrastructures may finally find in these economic operators a response to underfunding problems. On the other hand, institutional investors may find profitable opportunities in infrastructure projects. These will be outlined in the following paragraph.

Correspondence between institutional investors and social infrastructure investments

There is an ideal match between infrastructural investments and institutional investors necessities. Indeed, institutional investors respect the “Prudent Person” principle, which “stipulates that insurers may only invest in assets and instruments whose risks the undertaking concerned can properly identify, measure, monitor, manage, control and report and appropriately consider in the assessment of its overall solvency needs. All assets are to be invested in a manner that ensures the security, quality, liquidity and profitability of the portfolio as a whole” (BaFin, 2020).

Thus, institutional investors operate according to well-defined risk-return criteria, look for diversification opportunities and prefer long-term investments. However, they tend to operate in a low-interest rate environment due to long-term duration of their liabilities, and so, having difficulties in meeting future obligations.

This is why social infrastructure investments may represent an appealing opportunity for them: they tend to deliver cash flows that are constant and predictable over time, since these rely on public sector’s payments. The amount of the payment is agreed in advance and, usually, it is inflation-linked. Also, they display low volatility and a low sensitivity to market cycles, since demand for social infrastructures and essential services tend to be stable over time, even when economic crises occur; they display also limited correlation to other assets and are less exposed to market risk and systemic risks within capital markets; thus, they represent a compelling occasion for portfolio diversification.

This is why social infrastructure investments happen to be prudent investments corresponding to the risk appetite of most institutional investors. Indeed, they try to achieve the highest possible return with the lowest level of risk, over a prolonged time frame.

Institutional investors commitment to ESG criteria

Finally, another opportunity entailed by social infrastructure investments is represented by the possibility to boost the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) components of investors’ portfolios.

Indeed, most institutional investors have signed the UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI): the 2016 signers were more than 1,500 between investors and managers, totaling $60 trillion in AUM. By doing so, they “[…] recognise that applying these Principles may better align investors with broader objectives of society. Therefore, where consistent with our fiduciary responsibilities, we commit to the following:

Principle1: We will incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes.

Principle2: We will be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our ownership policies and practices.

Principle3: We will seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by the entities in which we invest.

Principle4: We will promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles within the investment industry.

Principle5: We will work together to enhance our effectiveness in implementing the Principles.

Principle6: We will each report on our activities and progress towards implementing the Principles” (PRI ASSOCIATION, 2006).

Indeed, in the same year, the European Parliament and Council Directive, IORP II (enforced in 2017), required pension funds to take ESG factors into consideration in their investment decisions and to increase their transparency for information disclosure. Wherefore, they were required to publish a Statement of Investment Principles, which reports how their investment choices involve ESG factors.

Lastly, institutional investors’ commitment toward ESG criteria has increased after COVID-19 pandemic. For example, a survey from BNPP AM (2020), which gathered responses from more than 100 European institutional investors and financial intermediaries, found that ESG have become even more relevant for 23% of the respondents, while 81% was already considering them in their investment choices.

Investment in EU and Juncker Plan

European institutions have already understood the fundamental role institutional investors can play in financing social infrastructures, consequently they tried to take progressive steps toward their further engagement. This is why, the European Commission launched in 2015 the Investment Plan for Europe, with three main objectives: “to remove obstacles to investment; to provide visibility and technical assistance to investment projects; and to make smarter use of financial resources” (European Commission Website); one of its final objectives was to increase institutional capital involvement in infrastructure financing.

To attain three goals, three pillars were developed:

- The creation of the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI): fund made up of €33.5 billion between guarantees and EIB’s own capital, able to mobilize, within 2020, €500bn of additional investment. EFSI enabled the realization of infrastructural projects without any increase in national public debt;

- The creation of the European Investment Advisory Hub and the European Investment Project Portal, with the objective of easing finances access to the real economy: this is achieved by linking private and institutional investors with “bankable” projects;

- Support the development of European and national regulations which are simpler, more supportive and predictable, hence aiming at removing regulatory barriers to investments across Europe.

Therefore, the Investment Plan for Europe aimed at a major involvement of institutional investors in the financing of infrastructure projects; however, only the 4% of the EFSI transactions approved by EIB were addressed to social infrastructures. The efforts of the Juncker Plan will be expanded by the following program, InvestEU, which, between 2021 and 2027 will have to trigger at least €650 billion to further boost investment, innovation and job creation. Moreover, after COVID-19 crisis, the program has been updated and the financial envelope addressing sustainable infrastructures has been doubled.

Institutional investors current investments in infrastructures

A 2019 survey by Preqin found that about 4000 infrastructure investors had nearly $600 billion capital invested in infrastructure globally at the end of 2019 (Merola, 2019) and other surveys found that many investors intend to increase allocations in these assets further in the future (Mercer, 2019/ E&Y, 2020).

However, despite this commitment, institutional investors’ asset allocation to unlisted and private infrastructure is still low: the previous cited survey by Preqin shows that the median asset allocation to infrastructure by reporting investor is around 2% for pension funds and foundations and around 1% for insurance companies, while non-reporting funds often hold no or few such investments. Moreover, the main target of these investors are still economic infrastructures and only a small fraction of their investments is on social infrastructures (e.g. about 4% of large pension funds’ infrastructure assets).

Notwithstanding the opportunity entailed by social infrastructures, institutional investors’ investments in the sector remain low, due to a number of investment constraints and barriers: for example, this is the case of an insufficient pipeline of projects, institutional investor’s inexperience with the construction risks management, which disfavor greenfield infrastructure investments and, finally, political and regulatory risks.

Key challenges for infrastructure investors

Situation in Italy

In Italy, institutional investors AUM raised by 112% between 2007 and 2018, passing from about € 404 billion to about € 859 billion; hence, passing from the 25% to the 49% of national GDP (Merola, 2019). Despite their rise being slower than in other European countries, they still represent a conspicuous pool of resources in search of investment purposes.

However, a survey carried out by Mercer, the European Asset Survey (2019), highlighted that national institutional investors still invest too little in the Country, most of all if compared to other EU Member States.

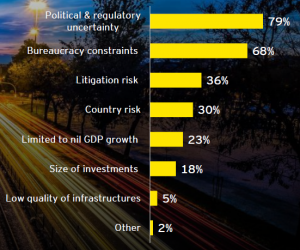

Indeed, Italy presents many barriers for their involvement. According to an Ernst Young report of 2020, Infrastructure Barometer, these are embodied mainly by political and regulatory uncertainty which characterize the national political landscape, by bureaucracy constraints, by litigation risks and country risks.

Main barriers for institutional investors in Italy

Furthermore, in the Country, there is still a limited pool of developed and suitable financial arrangements, which can favor their involvement; finally, there is not a supportive normative and regulatory framework.

Despite these criticalities, the report highlights that international institutional investors are increasingly considering to invest in Italy, mainly for the reasons reported below:

Institutional investors’ main motivations to invest in Italian infrastructures

With regard to social infrastructures, of the 71% of respondents that invested in the Italian market, only 11% invested in social infrastructures. Luckily, this percentage is rising, since 30% of respondents declared themselves to be interested in Italian social infrastructure investments in the future. Also, 59% of respondents expect competition for infrastructure investments and financing in Italy to increase in the next 12 months.

Hence, as the EY survey shows, international institutional investors’ attention is increasingly addressed toward the Italian infrastructural market; nonetheless, in order to foster their engagement, main criticalities will have to be resolved.

Conclusions

The article wanted to convey attention on the increasing amount of financial resources controlled by institutional investors in Europe in the last decade. Indeed, their engagement may represent an opportunity for national governments in search of financial resources necessary to support the development and construction of social infrastructures. Certainly, these assets are fundamental for citizens’ wellbeing, but, in recent years, they have suffered from profound underinvestment; ultimately, their situation became even more critical after COVID-19 spread.

Therefore, countries may exploit different, parallel solutions to address this gap: they may count on their public financial resources and address part of the gap all by themselves (however, this opportunity is precluded to most European Countries); they can increase their public debts and, finally, they can look at private capital coming from alternative investors’ class. One of these classes is represented by institutional investors, whose influence in financial markets is rising, together with their attention toward ESG and infrastructure investments. Thus, this match can reveal to be successful; the challenge is for national governments to remove barriers and create a supportive normative and regulatory framework.

Bibliography (B-E)

- BaFin 2020, Prudent Person Principle. Available online at: https://www.bafin.de/EN/Aufsicht/VersichererPensionsfonds/Kapitalanlagen/PrudentPersonPrinciple/prudent_person_principle_node_en.html#:~:text=The%20prudent%20person%20principle%20stipulates,of%20its%20overall%20solvency%20needs.

- BNP Paribas Asset Management, Comunicato stampa su indagine di BNP Paribas Asset Management su studio ESG. Available online at: https://docfinder.bnpparibas-am.com/api/files/26BC19E9-17C6-4CFC-9909-4943F366E198

- CUSUMANO N., Casalini F. and D’Arcangelo F.M., 2018. EU Financing Policy in the Social Infrastructure Sectors: Implications for the EIB’s sector and lending policy Final research report, SDA Bocconi, EIB, STARBEI, Milan, Italy. Available online at: https://institute.eib.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/EIB_Final-report.pdf

- EIB, 2018, EIB Investment Report 2018/2019, Luxembourg. Available online at: https://www.eib.org/attachments/efs/economic_investment_report_2018_key_findings_en.pdf

- ERNST & YOUNG 2020, EY Infrastructure Barometer Report- Italy;

- European Commission. Investment Plan for Europe. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/jobs-growth-and-investment/investment-plan-europe_en

Bibliography (F-P)

- Fransen L. del Bufalo G. and Reviglio E., 2018. Boosting Investments in Social Infrastructure in Europe, European Economy Discussion Paper, Luxembourg. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/dp074_en.pdf

- Inderst G., 2020. Social Infrastructure Finance and Institutional Investors – A global perspective, London, UK;

- Krišto J. and Stojanovic A.,2014. Impact of institutional investors on financial market stability: lessons from financial crisis, International Journal of Diplomacy and Economy Vol.2, Zagreb, Croatia. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264815558_Impact_of_institutional_investors_on_financial_market_stability_lessons_from_financial_crisis/link/59a3f6e60f7e9b4f7df3468d/download

- MERCER, 2019. European Asset Allocation Survey 2019, New York, USA. Available online at: https://www.uk.mercer.com/our-thinking/wealth/european-asset-allocation-survey-2019-e.html

- Merola F.,2019. Per una nuova politica degli investimenti: i fondamentali del cambiamento in una visione complessiva di policy, Arpinge, Rome, Italy;

- OECD, 2014. Institutional Investors and Long-term Investment Project Report. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/finance/OECD-LTI-project.pdf

- PRI Association, 2006. What is the PRI? Available online at: https://www.unpri.org/pri/about-the-pri

***

Autore dell’articolo*: Gloria Paronitti, Studentessa di Master in Management all’Università LUISS Guido Carli di Roma e Dottoressa in Global Governance all’Università Tor Vergata, Roma, Italia.

***

Nota della redazione del Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

Come sempre pubblichiamo i nostri lavori per stimolare altre riflessioni, che possano portare ad integrazioni e approfondimenti.

* I contenuti e le valutazioni dell’intervento sono di esclusiva responsabilità dell’autore.

Editor’s Note – Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

As always, we publish our articles to encourage debates, and to spread knowledge and original and alternative points of view.

* The contents and the opinions of this article belong to the author(s) of this article only.