What is happening in China? An overview about Uyghurs situation

The Uyghurs are a Muslim Turkish ethnic population representing one of the 56 nationalities recognized by the People’s Republic of China (PRC). They mostly live in the region of Xinjiang, which is an autonomous region of China since 1955 that has a strategic geographical position in the far west of the country. Indeed, Xinjiang borders 8 countries and has many natural resources, e.g. gold, oil, uranium, and gas. This is an area of tensions and interests, thus China has encouraged the immigration of Hans – main ethnic group in China – to impose its presence on the territory (Clarke, 2015). In 1949, the Hans represented only 6,7% of the Xinjiang population while in 1978, they represented 41,6% of the population (Zenz, 2020). The PRC wants to achieve territorial, political, economical, and cultural integration while the Uyghurs want their independence.

In the 1990s, the PRC accelerated an anti-religious campaign following a series of terrorist attacks. The politics of colonisation and acculturation in Xinjiang had provided fertile ground for the spread of extremism. The Chinese government claimed that while Uyghurs are originally Chinese, they were historically forced to be Muslim (Walden, 2019). After the 11 September attacks in the United States, China launched a repressive policy in Xinjiang against the separatists, labelling them as terrorists (Chung, 2002). One of the main groups of separatists is especially accused of collaboration with al Qaeda whereas they accused PRC of arbitrary arrest, torture, detention without public trial, and summary execution (Ibidem). Under cover of the war against terrorism, China took the opportunity to conduct an even more repressive policy against the Uyghurs.

An ongoing ethnocide

Some experts and non-governmental organizations (NGO) qualify the Chinese politic in Xinjiang as “cultural genocide” (Leibold, 2019). Yet, the notion of “cultural genocide” is not recognized as an international crime because this is not a threat of loss of life. In fact, it is rather a loss of culture that characterizes and identifies a population as a minority (Finnegan, 2020). Raphael Lemkin, who coined the notion of “genocide”, considers that the essence of a genocide is cultural (Lemkin, 1944). However, the final text of the Genocide convention limits the notion of genocide to physical and biologicals aspects (United Nation, 1948). Robert Jaulin, a French ethnologue, has developed the notion of “ethnocide” in 1970 to put emphasis on cultural aspect. He defines this notion as the systematic destruction of a culture through the process of decivilization (Jaulin, 1970). “In short, genocide kills people in their bodies, ethnocide kills them in their minds” (Clastres, 1974).

The PRC has forbidden Uyghurs language in public, indeed this language is “unpatriotic” according to a statement by the Chinese authorities (Byler, 2019). Moreover, to fight against “extremism”, the PRC sanctions Uyghurs’ “suspicious” behaviours such as not eating pork, wearing a headscarf, or praying (Leibold, 2019). Last but not least, Adrian Zenz, a German researcher, has uncovered in 2019 evidence of the separation of Uyghur children from their parents in state institutions. In conclusion, we can rightly qualify this as an ethnocide. The Uyghurs are prohibited from expressing cultural traits that differ from the Chinese Han model. Therefore, the PRC exercises high surveillance, for example, they send a member of the communist party in Uyghurs’ houses for a week per month. The aim is to monitor if they are living the Hans’ way of life (Pedroletti and Thiebault, 2020).

Camp of “re-education” and surveillance

In 2019, an investigation conducted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and exposed by seventeen international media channels reported the organisation of the mass detention camps in Xinjiang. On the basis of hundreds of pages which leaked the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) documents, the “China cables” reveal, inter alia, arbitrary detention, extreme detention conditions, and brainwashing. Officially, the PRC argues that there are camps of re-education to fight terrorism by providing education and vocational training to increase job opportunities and decrease poverty. The camps in Xinjiang expanded rapidly after the nomination, in August 2016, of Chen Quanguo, the new Communist Party Secretary of Xinjiang (Buckley and Ramzy, 2019). He has a strong reputation in ethnic policy innovations (Zenz and Leibold, 2017) based on extreme surveillance of the population. Therefore, between 2016 and 2017, over 90,000 new police and security-related positions were promoted under his authority (Zenz and Leibold, 2017).

The “China Cables” reveal how the police is using artificial intelligence and collecting data to target people for detention. In fact, the PRC has developed an advanced system of facial recognition to track and control the Uyghurs by their appearances (Mozur, 2019). Therein, the company Alibaba is accused by IPVPM – the world’s leading authority on video surveillance – and The New York Times to offer Uyghurs recognition as a “service”. According to their investigation, China users of Alibaba can send images or videos of a person that they consider as an Uyghur. Then, if they are confirmed to be Uyghur by the service of Alibaba, they get “flagged”. With this technology, the PRC government can identify and remove videos and photos of Uyghurs before they have important views. Other tech companies, Huawei and Megvii, are also accused of participating in the surveillance and repressive policy led by the PRC (IPVM, 2020).

Organ trafficking

For many years, China has harvested organs from death row inmates before announcing to the international community the end of this practice in 2015. Yet, in 2019, the United Nations (UN) urged to investigate organ harvesting in China. Indeed, Hamid Sami, a senior lawyer, declared in the Counsel to China Tribunal – an independent tribunal based in London – that it is a “legal obligation.” Among the victims, there are the Uyghurs (Health Europa, 2019). The French journalist Sylvie Lasserre denounces this organ trafficking of prisoners in Xinjiang camps (Lasserre, 2020). Furthermore, a survey conducted by the European deputy Raphael Glucksmann denounces a scheme of “halal” organ trafficking for the benefit of wealthy gulf buyers. This is why DNA, fingerprints, iris scans, and blood samples of all Uyghurs between 12 and 65 years old are taken in Xinjiang (Glucksmann, 2020).

Modern slavery

Between 2017 and 2019, more than 80 000 Uyghurs were transferred out of Xinjiang to work in factories across China, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. These factories supplied at least 82 well-known global brands like Apple, Samsung, Huawei, Sony, BMW, Volskwagen, Nike, Zara, and Gap (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2020). In factories, they live in “segregated dormitories, undergo organised Mandarin and ideological training outside working hours [and] are subject to constant surveillance.” Moreover, government documents proved that they are “assigned minders and have limited freedom of movement” (Ibidem). Another report revealed by Libération, BBC and Süddeutsche Zeitung denounces the conditions of Uyghur workers in the cotton fields in Xinjiang. This region produces 85% of the Chinese cotton, which represents 20% of the production of cotton in the world. The survey shows in particular that the salary is under the minimum local wage and some of the workers sleep on the ground and/or in the open air (Defranoux, 2020).

One of the arguments advanced by the PRC government to justify this forced labour is the poverty that affects considerably this peasant region. Some companies like Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein that were in collaboration with these factories took the decision to stop their commercial relationship with them. Indeed, following a mobilization on social networks led by the European deputy Raphael Glucksmann, a lot of brands preferred to detach their image from this scandal. This also reveals that our consumption and engagements have an impact on the Uyghurs’ situation: somehow, we are all responsible. Thus, this should lead companies to question their production chain.

PRC’s birth rate policy for Uyghur population

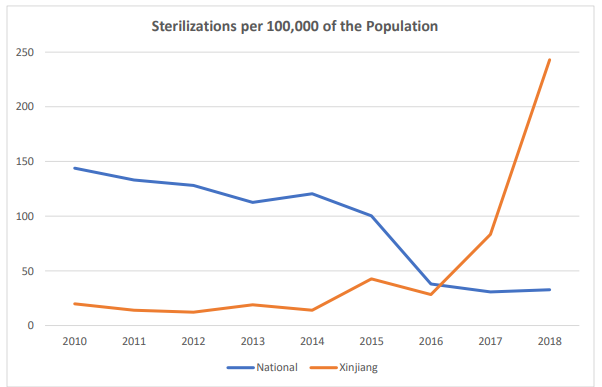

In China, there is a national policy of birthrates to control the overpopulation in the country. However, this policy conducts to dramatic societal consequences like sex-selective abortion (Hesketh et al., 2011). Officially, the PRC’s government financially sanctioned families with more than one or two children. In the region of Xinjiang, families are composed of more than one or two children, birth quotas are often disregarded. They prefer to take the risk of getting a fine over following this restriction (Zenz, 2020). Nonetheless, between 2015 and 2018, the rate of birth in the two largest prefectures in Xinjiang declined by 84 percent. Adrian Zenz denounces the “CPP’s campaign to suppress Uyghur birth rates in Xinjiang.” Indeed, there are documents of the Chinese government that punish violations of birth control by “extrajudicial internment in ‘training camps.’’ Moreover, other documents, studied by Adrian Zenz, reveal plans for a campaign of “mass female sterilization in rural Uyghur regions.”

Source : 2011-2019 Health and Hygiene Statistical Yearbooks, table 8-8-2.

In fact, we can see in the document that the rate of women sterilized in Xinjiang had considerably increased between 2016 and 2018. At the same time, the national curve stabilized with less than 50 per 100,000 sterilization. Other women are put on an IUD, a method of contraception, prompted or coerced by the government with a regular control. Chinese IUDs can only be removed through “surgical procedures by state-approved medical practitioners, with unauthorized procedures being punished with prison terms and fines”. Furthermore, during the “training camps”, a lot of women go through menopause or widowhood (Zenz, 2020). The Uyghurs have been subjected to human rights violations: every aspect of their lives are under control in order to dramatically reduce their presence in the PRC.

Conclusion

The PRC is pursuing an ethnic policy against the Uyghurs that flouts the most fundamental rights. This minority in China is being deprived of its culture, stalked, locked up, tortured, and exploited. In a globalized world, we are all responsible: our cellphones, our cars, our clothes and many other objects that we have are contributing to this human disaster. Our governments are also responsible for this deprivation of rights, due to their silence and even their actions.

On December 17, 2020, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the Uyghurs’ situation in China against forced labour and mass incarceration (European Parliament, 2020). They urged the PRC’s government to “immediately end the practice of arbitrary detentions without charge, trials and criminal convictions of Uyghurs.” They ask to “close all camps and detention centers for ethnic minorities victims of mass imprisonment” (European Parliament, 2020). This is a first step. However, China remains a great commercial power to which States fear to oppose head-on.

Bibliography [A-J]

Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2020. Uyghurs for sale.

Buckley Chris and Ramzy Austin, 2019. The Xinjiang Papers. “‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims”. The New York Times.

Byler Darren, 2019. “The ‘patriotism’ of not speaking Uyghur”. SupChina.

Clarke Michael, 2015. “China and the Uyghurs: The “Palestinization” of Xinjiang?”. Middle East Policy. Vol. XXII, No. 3.

Clastres Pierre, 1974. “De l’Ethnocide”. L’homme. Vol. XIV, No. 3 / 4.

Chung Chien-peng, 2002. “China’s “ War on Terror”: September 11 and Uighur Separatism”. Foreign Affairs.

Defranoux Laurence, 2020. “Ouïghours : esclavage moderne dans les champs de coton chinois.” Libération.

European Parliament, 2020. Violations des droits de l’homme en Chine, en Iran et en Égypte.

Finnegan Ciara, 2020. “The Uyghur Minority in China: A Case Study of Cultural Genocide, Minority Rights and the Insufficiency of the International Legal Framework in Preventing State-Imposed Extinction”. MDPI, Open Access Journal, Vol. IX, No.1.

Health Europa, 2019. China’s organ transplant crimes delivered to UN Human Rights Council.

Hesketh Hélène, Wang Xiao-Lei, Zhou Chi and Zhou Xu-Dong, 2011. “Son preference and sex-selective abortion in China: informing policy options.” International Journal of Public Health.

IPVM, 2020. Alibaba Uyghur Recognition As A Service.

IPVM, 2020. Huawei / Megvii Uyghur Alarms.

Jaulin Robert, 1970. La Paix blanche, Introduction à l’ethnocide.

Bibliography [L-Z]

Lasserre Sylvie, 2020. Voyage au pays des Ouïghours: de la persécution invisible à l’enfer orwellien.

Leibold James, 2019. “Despite China’s denials, its treatment of the Uyghurs should be called what it is: cultural genocide.” The conversation.

Lemkin Raphaël, 1944. Axis Rule in Occupied Europe.

Pedroletti Brice and Thibault Arnold, 2019. “« China Cables » : révélations sur le fonctionnement des camps d’internement des Ouïghours.” Le Monde.

Pedroletti Brice and Thibault Arnold, 2020. “Ces faux « cousins » chinois qui s’imposent dans les familles ouïgoures.” Le Monde.

Thum Rian, 2018. The Uyghurs in Modern China.

Mozur Paul, 2019. “One Month, 500,000 Face Scans: How China Is Using A.I. to Profile a Minority”. The New York Times.

Reix Justine, 2020. “Comment la Chine vend les « organes halal » de ses prisonniers Ouïghours aux riches.” Vice.

United Nations, 1948. “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations.”

Walden Max, 2019. “Xinjiang’s Uyghurs were enslaved and forced to convert to Islam, Chinese white paper claims”. ABC.

Zenz Adrian and Leibold James, 2017. “Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitization Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang.” The JamesTown Foundation. Vol. XVII, No.12.

Zenz Adrian, 2019. “Break Their Roots: Evidence for China’s Parent-Child Separation Campaign in Xinjiang”. The Journal of Political Risks. Vol. IX, No.7.

Zenz Adrian, 2020. “Sterilizations, Iuds, and mandatory birth control: the cop’s campaign to suppress Uyghur birthrates in Xinjiang”. The JamesTown Foundation.

Zhong Raymond, 2020. “As China Tracked Muslims, Alibaba Showed Customers How They Could, Too”. The New York Times.

Autore dell’articolo*: Sabine Hamonet, esperta in affari europei e relazioni internazionali del think tank Trinità dei Monti. Dottoressa in Studi politici presso Nouveau Collège d’Etudes Politiques; Master di studi europei e internazionali presso Université Sorbonne Nouvelle.

***

Nota della redazione del Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

Come sempre pubblichiamo i nostri lavori per stimolare altre riflessioni, che possano portare ad integrazioni e approfondimenti.

* I contenuti e le valutazioni dell’intervento sono di esclusiva responsabilità dell’autore.

Editor’s Note – Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

As always, we publish our articles to encourage debates, and to spread knowledge and original and alternative points of view.

* The contents and the opinions of this article belong to the author(s) of this article only.