Libya has been torn by conflict and foreign interventions since 2011, when a NATO-led military intervention toppled Gaddafi’s regime. Since 2014, the oil-rich North African country has been divided into Western Libya and Eastern Libya, with two rival administrations. In the last months, a shift in the Libyan conflict has captured worldwide attention and generated renewed hope for a ceasefire. In this regard, Turkey’s involvement in support of the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) has caused serious setbacks for Haftar and his self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA), for the first time since April 2019. As the GNA regained control over Tripoli, ceasefire talks are back on the negotiating table, signing a key moment in the Libyan conflict. In light of these events, this article aims to shed light on the causes of the conflict and its prospects for peace, with particular attention given to geopolitics and human rights.

Background on the Libyan conflict

In the past, Libya had one of the highest standards of living in Africa with free education and healthcare, thanks to its oil reserves (BBC, 2020a). Today, Libya is suffering from nine years of civil war, deep economic crisis and political and social chaos.

In order to understand what went wrong, it is necessary to go back to the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, when a controversial NATO-led intervention removed and killed Gaddafi. This opened a power vacuum in the country, as the Libyan militias that united in 2011 in their hatred for Gaddafi began fighting one another in an effort to gain national control (ibid.). These militias are a combustible mix, split along regional, ethnic and local lines and ideologically divided.

Gaddafi’s questionable strategy for maintaining peace over 42 years was to play these tribes off against each other (Al Jazeera, 2020a). Therefore, at the time of his gruesome death there was no functioning state left in Libya (Bowen, 2020). In 2016, former US President Obama admitted that his worst mistake as president was failing to prepare for the aftermath of Gaddafi’s overthrow (BBC, 2020a).

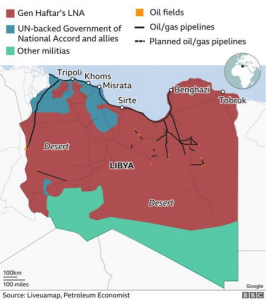

Libya is now divided into two rival administrations: the Tripoli administration known as the GNA in Western Libya, an internationally recognised and UN-backed government headed by Fayez al-Sarraj, and the Tobruk administration known as the House of Representatives (HoR) in eastern Libya. The latter includes members of parliament who won elections in 2014, which were later on ruled as unconstitutional by the Supreme Constitutional Court, which also urged the parliament to dissolve. On the other hand, the HoR criticise the GNA for being Islamist-oriented. Indeed, the Islamist trope is often used to delegitimise actors in conflict and justify violence (Megerisi, 2020)

Haftar, Libya’s warlord

The Tobruk administration in the East is loyal to General Khalifa Haftar, who has emerged from the conflict as Libya’s new strongman thanks to his control over the LNA militias. Haftar has an interesting past, as he originally helped Gaddafi seize power in 1969, becoming one of his top officials, to then fall out with him in the 1980s and move to the US for thirty years (BBC, 2020a). During that time he worked with the CIA on the American fight against Gaddafi and only came back to Libya in the 2011 in order to fight his older boss in the favourable context of the Arab Spring anti-government uprisings (ibid.)

Analysts have drawn parallels between Libya and Egypt, arguing that Haftar is ‘the el-Sisi of Libya’, referring to how military general el-Sisi in Egypt led a coup in 2013 to overthrow the legitimately elected president Morsi, becoming the new country’s president (ibid.)

Recent developments

Haftar and the LNA control the East and much of the South of Libya, two strategic areas in which Libya’s main oil fields are located (Al Jazeera, 2020c), while the GNA controls Western Libya. Thanks to Turkey’s support, the GNA has recently regained control over the capital Tripoli, which had been under Haftar’s control since April 2019. Tripoli is a strategic city, in which the only two institutions with permission to sell Libyan oil according to international agreements –i.e. the Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC) and the Central Bank- are based (Al Jazeera, 2020c). GNA’s victory in Tripoli allowed to resuming oilfield production after a months-long hiatus that halved Libya’s oil exports (ibid.).

Now that the GNA has the upper hand, Egypt, which is one of Haftar’s allies, advanced a peace proposal supported by other Haftar’s allies. However, the GNA and Turkey rejected the proposal as unilateral and asked instead for UN-led peace talks (Middle East Eye, 2020).

Nevertheless, the conflict has now moved into more localised fighting and small territorial gains, focusing over the strategic city of Sirte, rather than towards a political solution. The outcome of the fight over Sirte will tell whether the region of the oil crescent -where 80% of Libyan oil reserves are located- will ultimately fall under GNA or LNA control (Colombo, 2020). For the GNA, gaining control over Sirte would help secure and expand its support base by distributing oil revenues, especially as its eastern counterpart is unable to sell oil to international markets due to its lack of legitimacy (ibid.).

Indeed, it is largely impossible to understand the Libyan conflict without talking about the energy industry, as Libya is a key player in the natural gas market and it has Africa’s largest oil reserves (Bowen, 2020).

Foreign players in the Libyan battlefield

Despite the reopening of ceasefire negotiations between the GNA and the LNA, the UN has warned of possible conflict escalations due to foreign involvement (Al Jazeera, 2020c). Indeed, it could be argued that Libya has become a battlefield for a large number of international actors, which repeatedly ignore the UN arms embargo, sending fighters and weapons into Libya. Russia, the UAE, Egypt, Jordan and France support Haftar’s side, while Turkey, Qatar and Italy support the GNA.

According to the deputy head of the UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) Stephanie Williams, such heavy foreign involvement risks turning the Libyan conflict into a “pure proxy war” (Walsh, 2020).

Russia vs. Turkey: the two main spheres of influence

Among the variety of foreign players involved in Libya, Turkey and Russia are arguably the two main powers involved. Both Russia and Turkey are trying to assert their spheres of influence in the region as major powers. It is interesting to notice that the opposition dynamic between Russia and Turkey in Libya is parallel to that in Syria, where the two countries also support opposing forces (Yildiz, 2020).

At the heart of the proxy conflict in Libya is a “labyrinth of mercenary recruitment” from Russia and Turkey (Trew, 2020), characterised by wealthy foreign patrons and thousands of soldiers-for-hire deployed on both sides, including many targeted from Syria (ibid.).

Russia and the Wagner fighters

UN investigators believe at least 1200 Russian mercenaries were hired by Russian nebulous private military companies with ties to Russia’s Ministry of Defence and known as Wagner, along with somewhere between 800 to 2000 Syrian fighters and over 2000 Sudanese fighters in support of Haftar (Trew, 2020). Putin has denied Russia’s involvement, arguing that Wagner militias do not represent the Russian state (ibid.).

However, some have argued that Russia has been deploying Wagner fighters rather than the official military in over sixteen countries, as part of a safer and cheaper strategy to expand its influence across the Mediterranean and Africa, thus reducing accountability (ibid.).

Turkish interests in Libya

Turkey supplied the GNA with a few hundred of its own forces and as many as 3,000 to 6000 of its Syrian mercenaries. Back in November 2019, Erdoğan signed a controversial military and security memorandum of understanding (MoU) with al-Sarraj, establishing “18.6 nautical miles of a continental shelf and a Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) boundary line between the two countries” (Oruç, 2020). However, legal experts have argued that the MoU between Ankara and Tripoli is at odds with international law and it is unlikely to be observed, as it violates the rights of other countries in the region, such as Crete (Johnson, 2019)

Nevertheless the Turkey-Libya maritime deals generated alarm in the EU, leading to the signing of the EastMed Pipeline deal between Israel, Cyprus and Greece in early January 2020. The EastMed Pipeline would reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, transferring gas from Israel and Cyprus to Greece and then Italy, completely excluding Turkey (Oruç, 2020).

In addition, Turkey’s involvement in Libya can also be understood as a way to get extra leverage on Europe, with Libya being a major ‘launch pad’ for African migration into Europe, similarly to Syria (Yildiz, 2020)

What is the role of Europe?

The EU has been engaging in intensive contact, frequent training and capacity-building activities with the militias in Libya (Varvelli & Villa, 2019), while also launching Operation IRINI to enforce the UN’s arms embargo in the country (Girardi, 2020).

However, the scope and credibility of EU’s role in Libya is crucially limited by the fact that France and Italy are supporting opposite sides in the conflict. The two European countries both see Libya as a key partner in reducing and/or haltering migration flows from Africa to Europe (BBC, 2020c).

In this regard, Italy has signed a MoU with Libya with the main aim of reducing migration flows from Africa. Moreover, Italy has energy interests in Libya, as large natural gas pipelines go from Libya and Algeria to the south of Italy. Eni, the biggest energy company in Italy, has been a key player in North Africa for over sixty years.

Overall, the EU has contributed to producing an unsustainable security and political situation in Libya by prioritising its own short-term goals of reducing migration and guaranteeing European energy security (Varvelli & Villa, 2019). However, in the long run such approach is detrimental to the EU’s own interests, which in turn depend on Libya’s political and security conditions (ibid.).

Human rights violations

The real losers of the Libyan conflict are the Libyan people. According to the UN, more than 200,000 Libyans are internally displaced and 1.3 million need humanitarian aid (BBC, 2020a).

People in Libya do not feel safe, as militias arbitrarily detain thousands of people, take hostages for ransoms and commit torture and abuses (Amnesty International, 2019a). Journalists, politicians and activists are often harassed and detained, while the judicial system was crucially undermined (ibid.). The Libyan authorities have also failed to protect women from gender-based violence by armed groups (ibid.).

The main causes of civilian casualties are ground fighting, targeted killings, airstrikes, and improvised explosive devices (UNSMIL, 2020a). In particular, an increase in indiscriminate shelling on civilian-populated areas has resulted in a 45% increase in civilian casualties from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the period between 1 January and 31 March 2020 (ibid.). Healthcare facilities are damaged and there is a shortage of medicines, limiting Libya’s ability to cope with COVID-19 (UNSMIL, 2020b).

The conflict has also aggravated the already abhorrent conditions of 5,000 migrants and refugees held in Libyan detention centres, where they are victims of torture, rapes and abuses (Amnesty International, 2019b). Migrants and refugees are often exposed to arbitrary arrest and abduction by militias and they are often victims of human trafficking (Amnesty International, 2020).

While both sides in conflict are guilty of reckless treatment of civilians, Haftar and his forces have committed more documented abuses that could also be recognised as war crimes (Bowen, 2020; Human Rights Watch, 2020). According to UNSMIL, Haftar’s forces were responsible for the majority of killings of civilians between April and May 2020 (Walsh, 2020) and multiple mass graves have been found in Tarhuna and other areas recently retaken from Haftar’s forces by the GNA (Al Jazeera, 2020d).

Libyan prospects for peace: what is happening next?

Haftar’s setback is a crucial turning point in the Libyan conflict, as it could either produce an escalation of the conflict or a ceasefire.

Indeed, there is still a long road ahead towards a long-lasting peace in Libya. German academic Lacher (2020) has pointed out that Turkey and Russia might prefer a partition rather than a strong and unified government that would force foreign troops to leave and reduce their influence. Lacher (2020) goes as far as saying that Haftar’s sudden defeat in Tripoli could be the result of a closed-door agreement between Erdoğan and Putin, a first step towards the partition of Libya. Indeed, if Russia and Turkey maintain the status quo in Libya they could coordinate a de-facto and possibly de-jure division of the oil-rich country (Yildiz, 2020).

However, a long-lasting peace solution for Libya must ultimately lie in Libyan hands. This is why this is a crucial moment for the GNA to present itself as the right governments for all Libyans, not just the people in Tripoli (Megerisi, 2020). The international community including the EU and Italy should support this goal and help preventing Libya from becoming ‘Syria 2.0’.

To end on a positive note, the establishment of an international Fact-Finding Mission to Libya (FFML) by the UNHRC is an important first step towards generating accountability for human rights violations committed in the Libyan conflict, which is essential pre-condition for peace (UNSMIL, 2020c).

Bibliography (A-G)

Al Jazeera (2020a). Has Khalifa Haftar’s campaign in Libya failed?. (online). Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/insidestory/2020/06/khalifa-haftar-campaign-libya-failed-200605204021650.html (Accessed 21 June 2020).

Al Jazeera (2020b). Libyan court rules elected parliament illegal. (online). Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/11/libyan-court-suspends-un-backed-parliament-201411691057750925.html (Accessed 25 June 2020).

Al Jazeera (2020c). Turkey’s foreign minister visits Libya for talks with GNA. (online). Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/turkey-foreign-minister-visits-libya-talks-gna-200617163735710.html (Accessed 21 June 2020).

Al Jazeera (2020d). Libya: Haftar’s forces ‘slow down’ GNA advance on Sirte. (online). Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/libya-haftar-forces-slow-gna-advance-sirte-200611061626411.html (Accessed 20 June 2020).

Amnesty international (2019a). Libya 2019. (online). Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/middle-east-and-north-africa/libya/report-libya/

(Accessed 17 June 2020).

Amnesty International (2019b). Europe’s shameful failure to end the torture and abuse of refugrees and migrants in Libya. (online). Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/03/europes-shameful-failure-to-end-the-torture-and-abuse-of-refugees-and-migrants-in-libya/ (Accessed 16 June 2020).

Amnesty International (2020). Libya: Fact-finding mission to investigate crimes is a welcome step towards ending impunity. (online). Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/06/libya-factfinding-mission-to-investigate-crimes-is-a-welcome-step-towards-ending-impunity/ (Accessed 22 June 2020).

BBC (2020a) Why is Libya so lawless?. (online). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-24472322 (Accessed 15 June 2020).

BBC (2020b). Libya conflict: GNA regains full control of Tripoli from Gen Haftar. (online). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52920373 (Accessed 8 June 2020).

BBC (2020c). Khalifa Haftar: The Libyan general with big ambitions. (online). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-27492354 (Accessed 23 June 2020).

Bowen, J. (2020). Libya conflict: Russia and Turkey risk Syria repeat. BBC News. (online). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52846879?intlink_from_url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world&link_location=live-reporting-story (Accessed 22 June 2020).

Colombo, M. (2020). Haftar’s setback. Libya: As Fighting Escalates, Stalemate Looms. ISPI. (online). https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/libya-fighting-escalates-stalemate-looms-26437 (Accessed 20 June 2020).

Girardi, A. (2020). La vendita delle navi militari all’Egitto è uno schiaffo alla famiglia Regeni. E riguarda tutti noi. (online). Available at: https://www.fanpage.it/politica/la-vendita-delle-navi-militari-allegitto-e-uno-schiaffo-alla-famiglia-regeni-e-riguarda-tutti-noi/ (Accessed 20 June 2020).

Bibliography (H-Y)

Human Rights Watch (2020). Libya: Apparent War Crimes in Tripoli. (online) Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/16/libya-apparent-war-crimes-tripoli (Accessed 20 June 2020).

Johnson, K. (2019). Newly Aggressive Turkey Forges Alliance With Libya. Foreign Policy. (online). Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/12/23/turkey-libya-alliance-aggressive-mideterranean/ (Accessed 16 June 2020).

Lacher, W. (2020). The Great Carve-Up. Libya’s Internationalised Conflicts after Tripoli. SWP Comment 25. (online). Available at: https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2020C25/ (Accessed 22 June 2020).

Megerisi, T. (2020). Webinar: Libya: Political Fragmentation, War and Foreign Intervention. Chatam House. (online). Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/event/webinar-libya-political-fragmentation-war-and-foreign-intervention (Accessed 26 May 2020).

Middle East Eye (2020). Libya unity government calls Egypt threat ‘declaration of war’. (online). Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/libya-unity-government-calls-egypt-threat-declaration-war (Accessed 19 June 2020).

Oruç, M. Ş. (2020). After Turkey-Libya deal, Greece and Israel can no longer exclude other coastal states. Daily Sabah. (online) Available at: https://www.dailysabah.com/columns/merve-sebnem-oruc/2019/12/11/after-turkey-libya-deal-greece-and-israel-can-no-longer-exclude-other-coastal-states (Accessed 23 June 2020).

Trew, B. (2020). Inside the murky world of Libya’s mercenaries. Independent. (online). Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/libya-war-haftar-gna-syria-russia-wagner-uae-tripoli-a9566736.html (Accessed 20 June 2020).

UNSMIL (2020a). Escalation in ground fighting drives up civilian casualties in first quarter of 2020. (online). Available at: https://unsmil.unmissions.org/escalation-ground-fighting-drives-civilian-casualties-first-quarter-2020 (Accessed 22 June 2020).

UNSMIL (2020b). UNSMIL expresses grave concerns over the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Tripoli and its surroundings, and in Tarhouna. (online). Available at: https://unsmil.unmissions.org/unsmil-expresses-grave-concerns-over-deteriorating-humanitarian-situation-tripoli-and-its (Accessed 22 June 2020).

UNSMIL (2020c). Statement by UNSMIL welcoming establishment of Fact-Finding Mission to Libya. (online). Available at: https://unsmil.unmissions.org/statement-unsmil-welcoming-establishment-fact-finding-mission-libya (Accessed 22 June 2020).

Varvelli, A. and Villa, M.(2019). Italy’s Libyan Conundrum: The Risks of Short-Term Thinking. ISPI. (online). https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/italys-libyan-conundrum-risks-short-term-thinking-24469 (Accessed 22 June 2020).

Villa, M. (2016). In for the Long Haul: Italy’s Energy Interests in Northern Africa. ISPI. (online). Available at: https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/long-haul-italys-energy-interests-northern-africa-15198 (Accessed 21 June 2020).

Walsh, D. (2020). In Stunning Reversal, Turkey Emerges as Libya Kingmaker. The New York Times. (online). Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/21/world/middleeast/libya-turkey-russia-hifter.html (Accessed 17 June 2020).

Yildiz, G. (2020). How (and Why) Turkey Strengthened Its Grip on Libya Despite Covid-19. ISPI. (online). Available at: https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/how-and-why-turkey-strengthened-its-grip-libya-despite-covid-19-26381 (Accessed 18 June 2020).

***

Autore dell’articolo*: Laura Mariani, studentessa MSc International Relations Theory presso LSE e laureata BA (Hons) presso School of Politics and International Relations of the University of Kent. Esperta di gender in politica internazionale del Think Tank.

***

Nota della redazione del Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

Come sempre pubblichiamo i nostri lavori per stimolare altre riflessioni, che possano portare ad integrazioni e approfondimenti.

* I contenuti e le valutazioni dell’intervento sono di esclusiva responsabilità dell’autore.

Editor’s Note – Think Tank Trinità dei Monti

As always, we publish our articles to encourage debates, and to spread knowledge and original and alternative points of view.

* The contents and the opinions of this article belong to the author(s) of this article only.